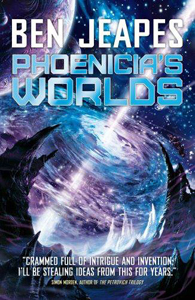

Except that, okay, they didn’t. But in an indirect way they did inform the development of Phoenicia’s Worlds.

Except that, okay, they didn’t. But in an indirect way they did inform the development of Phoenicia’s Worlds.

In the early 1940s, Britain stood alone against the Third Reich, one small island facing a continent beneath the bootheel of a fascist dictatorship, with but a narrow stretch of water between them. If Britain fell then so would European civilisation.

So, naturally, everyone on the British side pulled selflessly together to fight the common foe, right?

Did they hell. The various intelligence and covert organisations whose job it was to fight Nazi Germany spent half their time fighting each other in an endless squabble for resources, rights and precedence. Read Leo Marks’ Between Silk and Cyanide – it makes for jaw-dropping reading. Things got to the point where the SOE operation in the Netherlands was so compromised that we were literally dropping agents straight into the hands of the Gestapo, and Marks knew this but he couldn’t get anyone to believe him. Or, if they believed, to care about it.

[Don’t just take Marks’ word for it. I’ve read the memoir of his opposite German number in the Netherlands, Hermann Giskes, who backs it up – and comes across in fact as much less of a monster than Marks imagined.]

And yet, if you had actively put it to one of those idiots in London that their activities were at best hindering our war effort and at worst helping the enemy’s, they would have been genuinely outraged at the suggestion. No one was actively, consciously betraying their country. As far as they were concerned they were all 100% patriots doing what was best for everyone.

So, take that thought and hold it: the ability, nay inevitability of human beings to concentrate on the small picture rather than the big and convince ourselves that it’s for everyone’s good.

Related to this is an even less rosy aspect of human nature: our ability to fixate so firmly on one unacceptable option that any other option, even if infinitely more unacceptable, becomes preferable. “X did Y but they achieved Z”: how many times have you heard that? It’s a false dichotomy: it becomes, in the mind of the apologist, a straight choice with No Other Way. Thatcher destroyed whole communities but she saved the economy. Stalin murdered millions but he modernised the USSR. (And no, I’m not equating Thatcher with Stalin – please.)

And any apologist for the late Iron Lady’s good friend Augusto Pinochet – and there are many of them – will sooner or later trot out the line “but he saved Chile from Communism.” Pinochet isn’t alone in the ranks of saving-the-world-from-Communism dictators but, for some reason, he is the one that has always particularly got my goat.

It is, to borrow Captain E. Blackadder’s pithy critique of pre-WW1 foreign policy, bollocks.

It was bollocks in Chile and it was bollocks throughout South America for every right-wing dictatorship propped up by the west because Communism was perceived as the only alternative. Bollocks, bollocks, bollocks.

Here is a strange fact about Communism that no paranoid right-wing loon ever seems to understand: no nation has ever turned to it out of perversity, and it has never been inevitable. What does it is desperation. You don’t want to be rich, you just want to have enough to look after your family, but you are so poor and the system so rotten that this will never happen no matter how much hard, honest work you put in. Then along come the Communists who say they will build schools and hospitals. Meanwhile the government grinds you into the dirt and expects you to be grateful for the privilege. So who do you turn to? You don’t know that the Communist’s promises will turn out to be pie in the sky. All you know is what you have now, and pie in the sky is better.

As the British proved so successfully in Oman – round about the time the Americans were pursuing their arguably less successful anti-insurgency policies in Vietnam – you fight Communism by being better. The Communists say they will build schools and hospitals. You make sure that the right side does build schools and hospitals. They surrender a little of their wealth and power – just a little – and, yes, military action is taken against the small minority of hardline insurgents. And you win. Pinochet and his vile ilk could have turned back the tide almost overnight by following this course of action.

But no. That would have meant being slightly more left wing, which was out of the question. Thus, to save this ghastly fate befalling the country, it became okay for a government to turn on its own people, spy on them, torture them, murder them, because the alternative would have been perceived as Communism – which it wouldn’t have been, of course, just a very mild case of social democracy – and that would have been totally unacceptable.

Humans, eh?

And so I came to write Phoenicia’s Worlds.

I didn’t write it to write about these themes and there are no overt references to either of the above cases in the novel. It certainly isn’t a commentary on or critique of the War Against Terror or the austerity package that is meant to save us all from a debt-ridden fate worse than death; I actually started to write Phoenicia’s Worlds before 9/11 so nothing more recent than that was on my mind. Instead, these two excerpts exemplify beliefs about human nature that are so entrenched within my being that, when the basic scenario of a beleaguered planet struggling for survival suggested itself, I knew exactly how people would react to it. And that was why I felt it would make a good novel.